In early September, US cable provider Altice USA and Rogers Communications made a joint bid to acquire Cogeco Communications and its parent Cogeco Inc (I will refer to both as Cogeco). The proposed deal would have Altice acquiring Atlantic Broadband, the 9th largest cable provider in the US, and Rogers, Cogeco’s largest shareholder, acquiring the Canadian assets, mainly a cable footprint in Ontario and Quebec and giving Rogers an entry into Quebec. The deal was quickly rejected by Cogeco with President Louis Audet stating Cogeco was definitively not for sale. Despite this categorical rejection, the would-be buyers increased their bid by about 10% to $11 billion in mid-October. Not surprisingly, the increased offer was again summarily rejected by the Audet family.

Altice’s motivation in acquiring Atlantic Broadband is simple: add a complementary portfolio of high-quality assets at a fairly low price, in part by bribing the Audet family. I don’t have much more to say about it, but the Canadian side of the deal is more interesting to me and is a good illustration of the Canadian telecom landscape.

Background on the Canadian telecom industry

A common theme in Canadian business is that low population density across a massive geography makes it tough and expensive to achieve economies of scale. The telecommunications industry is no different: Canada’s low population density relative to other countries means that all else equal, it is more costly for a cable provider to connect each customer in Canada relative to those parts of the world where higher population per square kilometer naturally lends itself to a consolidated industry structure. For the same reasons in the US, particularly in the more thinly populated mid-west and western states, there is minimal incentive to build a cable network across another company’s footprint and in most places in Canada, there are no more than two options for cable internet: likely one of the “Big 3” Rogers, Telus, or BCE, plus a handful of regional competitors such as Cogeco, Shaw, and Eastlink. Given Cogeco’s overlapping position with BCE in the smaller cities in Ontario and Quebec, this is a perfect complement to Rogers’ cable footprint and one that Rogers has long desired to own.

The Big 3 also have a 90% market share in wireless, and control most of the necessary radio spectrum which makes cellular and wireless service possible. Each sells wireless service under its flagship brand as well as discount “flanker” brands.

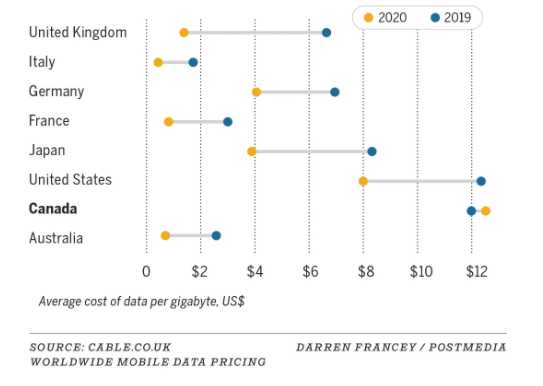

The dominant market positions of these companies have led to accusations of monopoly power, and indeed, Canadian wireless rates are among the highest in the world:

There is little doubt that internet access is an essential good today, so the main job of the CRTC, the Canadian regulator, is to balance affordable internet access (particularly in rural areas) with investment in telecommunications infrastructure by the majors. As discussed above, the difficult geography lends itself to a consolidated market structure, so high prices can be viewed as a function of the higher cost of building out wireless networks in Canada. As an example of this, in 2008 Canada held a special spectrum auction exclusively for new entrants in the wireless space, leading to a handful of new wireless companies including Wind Mobile, Public Mobile, and Mobilicity. Since then, Public Mobile and Mobilicity have been acquired in distress by Telus and BCE respectively, and Wind Mobile (now known as Freedom Mobile) has been acquired by Shaw Communications. Clearly owning spectrum is not enough to allow new entrants to battle deeply entrenched competitors.

As such, it is still no surprise that every quarter, Rogers, BCE, & Telus remind the CRTC of the need for a regulatory regime that supports investment whether it be regarding wholesale internet rates, basic TV bundles, or maximum wireless contract lengths.

“Just as our resilient networks provide the digital scaffolding during this health crisis, our country’s technology infrastructure will underpin Canada’s recovery. If connectivity was a lifeline during COVID-19, it will be the bottom line to Canada’s recovery. Today, the digital economy is the economy and our country’s tech-driven recovery will require the right investment-oriented regulatory environment. This is one of the most important lessons we can take from this moment.” Rogers Q2 2020 Earnings Call

Given the essential nature of telecommunication services and a regulatory regime that balances pricing with investment, the major Canadian telecoms can be viewed as safe utility stocks earning stable returns on equity.

Back to Cogeco

In March, the CRTC announced it was exploring the idea of mandating MVNO (Mobile Virtual Network Operator) access for the wireless networks. In plain language, this means that just like with cable, anyone will be able to purchase wireless services from the Big 3 at a wholesale price for resale.

A common view in the US is that as wireless speeds get faster, the lines between wireless and fixed hard-wired internet will blur, leading to consolidation of wireless and cable/fibre optic providers. In Canada, the major wireless providers are also the major cable providers, so from one perspective, Canadian telecoms have a head start in providing a unified product offering and managing their network on a combined basis. One hint of this was in February 2020 when Telus announced it would report the wireline and wireless segments on a combined basis as a single “telecommunications” segment:

“This change is how we will grow and manage our business and continue to build our converged network technologies, and the commercialization of fixed wireless solutions has made it increasingly difficult to distinguish between our wireline and wireless operation and cash flows, and the assets in which they use.” Telus Q1 20 Earnings Call

There are highly synergistic benefits of being able to offer both wireless and cable: enhanced marketing opportunities, simplified customer service and pricing, better network management, resulting in a stickier and more profitable customer relationship overall.

The heavy fixed costs required to build out a wireless network means that it is nearly impossible for a smaller hard-wired only competitor like Cogeco to build an adequate wireless network from scratch without incurring heavy losses. It goes without saying that mandatory MVNO access is a tremendous opportunity for Cogeco to add wireless service to its network to complete its product offering, and Cogeco said as much in a conference call after the rejection:

“There’s a timing element of this in terms of what’s going on at the CRTC. As you know, we are attempting to get into the wireless space and acquire spectrum over time. It’s not enough to launch an operation and we’ve proposed a hybrid MVNO framework to the CRTC which is being reviewed. We’re expecting some response from the CRTC as an industry eventually during the process of doing it now. So, obviously, taking Cogeco out of the equation for Rogers, it’s probably part of the equation to launch a hostile bid right now” Cogeco at the BMO Capital Markets Media & Telecom Conference

The “hybrid MVNO” model as proposed would only allow companies with existing telecom infrastructure to resell wireless services. Since Cogeco is essentially the only meaningful broadband company without wireless services (other regional players like Shaw and Quebecor both own spectrum), Cogeco’s proposal is simply for the CRTC to allow Cogeco to be the 4th national wireless player. This allows Cogeco to both play defense by increasing its service’s stickiness compared to third-party internet resellers, but also to go on the offensive by adding wireless services to its bundle. Cogeco has for years sought for the CRTC to regulate wholesale pricing to allow it to be the 4th national competitor and it makes no sense for Cogeco to sell out at a time when its long-desired prize is finally in sight.

What does this mean for existing players?

Regardless of what happens, regulators have long been looking for ways to increase wireless competition in Canada. However, in 2015, the CRTC studied and decided against mandatory MVNO access due to concerns that this would lead to underinvestment in wireless networks. The Competition Bureau had chimed in with its view that a facilities-based MVNO model (i.e. allowing new challengers to use MVNO access as a bridge to build up their own networks) would be superior to allowing wide open access for anyone to build a wireless business.

During COVID, each of the Big 3’s stock prices have underperformed in part because of lower international and roaming fees, which comes on the heels of the launch of unlimited data plans, which have reduced overage fees. This could be a blessing in disguise that regulators consider, especially given the upcoming 5G investment cycle. Rogers, Telus, and Bell have already warned about heavy job losses and reduced capital investment in the case of a negative ruling.

Despite the dire warnings from telecoms, it is very unlikely that implementation of mandatory MVNO access would harm the incumbents materially. The difficult geography and established position of incumbents means that only existing players have enough capital and scale to invest in a full build out of 5G and beyond. Regulators understand this and will likely include carrots for increased investment in infrastructure by the Big 3 if MVNO access is mandated. Furthermore, the launch of unlimited data plans substantially restricts the market of customers who would be profitable for a standalone MVNO, and limits the opportunity to low-data-using customers since the MVNO would pay wholesale rates on a per-usage basis. This will increasingly be true as data consumption and applications grow under 5G. New competitors also lack the distribution footprint and bundling capabilities of additional services and content that the incumbents enjoy.

At the end of the day, the reality of business in Canada is that even regulation cannot overcome the scale advantages that incumbents enjoy due to Canada’s low population density, whether the industry is supermarkets, retailers, or telecoms.