Cineworld acquires Cineplex & the future of the cinema

This blog will be split into two parts: Part 1 will discuss the challenges the theatre industry faces in North America and what the future will look like. Part 2 will discuss the Cineworld acquisition of Cineplex and what this means for moviegoers in Canada.

Summary

- Theatre attendance is declining given the massive amount of content available on subscription video-on-demand (SVOD).

- Producers are making less content for theatres given both attendance interest and the creativity allowed in episodic shows.

- Disney’s support for the traditional release window comes with a silver lining for theatres in the form of harsh terms, particularly with the repeal of the Paramount Rules.

- Theatre chains can adapt by dropping their resistance over the release window and by growing their subscription passes.

Movie attendance is in structural decline

The headwinds facing the theatre industry in North America (US and Canada) are well-known though I believe most people do not appreciate the true predicament that cinema chains are in today.

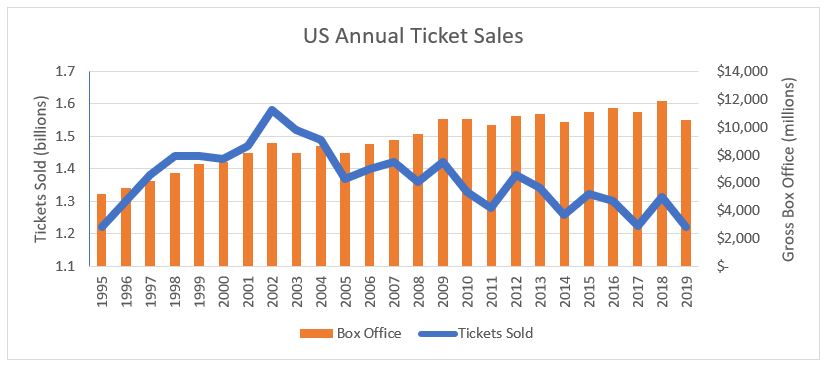

Total US theatre attendance peaked in 2002 (a year with Spider-Man, Star Wars, Harry Potter, and The Lord of the Rings), and has been falling ever since. You can see from the chart below that theatre attendance started falling before Netflix’s streaming service (2007) and YouTube (2005) were invented. The theatre industry has offset the decline by raising ticket prices to a record box office (not adjusted for inflation) in 2018: over the last 20 years, ticket prices have risen by about inflation plus 1% annually.

The recent rise of Netflix and SVOD is really a continuation of the same story over the last 50 years: improving technology and convenience leading to more ways to consume content. Before broadcast TV was invented, the cinema was literally the only place someone could watch content and over 60% of people went to the cinema every week. Today, the average person goes to a theatre only once every three months.

Broadcast TV, cable TV, the VHS player, PVRs, the DVD player and, more recently, the Internet, have given options and control to people for how and where content can be consumed. At the same time, large screen TVs and surround sound systems continue to get bigger, better, and cheaper. Each iteration of technological improvement chips away at the differentiated experience (both from a content and technological level) that came from going to the movies. As such, the movie theatre’s role has declined first from being the only place to watch any movie, then to becoming the best place to watch, and now just to being another option for a date or a family trip.

Today, the reason why you would go see a movie at a theatre vs finding something random on Netflix is because you want to go out, or because the movie truly needs to be experienced on a big screen. For most people, this usually means tentpole blockbusters in space or flashy superhero action sequences where you can “escape” with your friends and family for 2 hours. On the other hand, apart from maybe being a bit darker, there is not anything that different from watching a romantic comedy in a movie theatre vs your own home. As a result, action films and kids films have soared in market share at the expense of drama, and especially comedy and romantic comedy, which have fallen off a cliff in theatre viewership.

Studios and producers are correspondingly changing their production strategies in light of the changing attendance tastes.

Movie and content production is changing

Over the last decade, theatre chains have routinely blamed Hollywood for weak film slates that fail to excite attendance. The reality is that the continual shift in viewing habits has made Hollywood less reliant on the box office for revenue and even more so in a world where streaming services like Netflix and Amazon are fighting for content and talent to fill their shows. Netflix’s projected content spend of $15b in 2019 alone will be bigger than the entire US box office this year.

For every major studio today, the box office is a minority of the revenues earned from a movie[i]:

Licensing today makes much more money for the studios than the box office and, as a result, studios have prioritized content for SVOD at the expense of theatrical movies. Already we saw Disney bypass the theatre and launch The Lady and the Tramp on Disney+. At the 2019 Code Conference, Michael Nathanson of MoffettNathanson predicts the media industry will spend another $20b through 2023 in the land grab for digital distribution:

“What’s going to happen over the next 5 years is that the industry is going to create another Disney in order to try to win the hearts and minds of all those consumers who are cutting the cord”

MoffettNathanson’s Michael Nathanson at Code Media 2019

We’ve already discussed the shift in consumption towards blockbusters and kids shows at the theatre with studios shifting their content budgets accordingly. SVOD however leads to an even larger secular production trend: away from movies and towards episode shows.

At the core, scripted content is around creating and telling stories. After Netflix changed the industry by releasing all episodes of TV shows simultaneously, episodic shows essentially became longer movies that enable deeper and richer characters and storylines. This is especially effective for genres such as comedies and dramas, hence the decline in theatre viewership of these genres. Directors and actors/actresses loved both the creativity allowed and the dollars dangled to produce shows for SVOD, while resenting the rise of the Marvel blockbuster which reduces creativity and shifts consumer recognition from the director/actor/actress towards the brand while saving money for the studio (does anyone really care who’s behind Iron Man’s mask?).

“Movies in many ways have to be finished, (in episodic television) there’s a never-ending kind of storytelling which gives a lot of freedom to the creator and I think that’s one of the reasons why you see a lot of great moviemakers turning to television. It was a medium before that they didn’t feel would satisfy them because they didn’t have the scale or scope that they’re used to which is no longer the case. Now it gives them the ability to tell stories in a much more luxurious way and maybe even a more organic way, sometimes you don’t know really how a story will end or should end and you just kind of let it unfold and it comes to you as you’re creating it or as the audiences react to it.”

Bob Iger, Interview with The Star Wars Show

Today, no studio is focused on increasing the volume of content for the theatre. The raw number of movies released by the Big 6 studios has fallen from about 110 movies per year in the mid 2000s to down around 90 per year since 2010. This is especially true for comedies and romantic comedies, which the Big 6 have essentially stopped making. In 2019, the Big 6 only released two romantic comedies (Isn’t it Romantic, Last Christmas). The producers and directors have of course flocked to Netflix.

For a movie theatre, the number of movies matters more than the box office. It’s attendance that drives the high margin concession sales and pre-screen advertising and fills unused screens.

Given lower interest in the theatre from both consumers and producers, studios continue to put pressure on the release window to allow them to monetize films as quickly as possible. Year in and year out, studios continue to push for early video-on-demand and will likely increase this pressure given the weakening position of theatres and the increasing pressure from streaming services like Disney+ and Netflix.

Disney as the partial savior

Disney is the only studio that has so far insisted on maintaining the theatrical release window, and the acquisition of 21st Century Fox gave the “preserve the release window” group a boost as Fox had been in favor of premium video-on-demand. However, this support comes with a silver lining: an unprecedented level of market share combined with a favorable regulatory environment. After the combination with Fox, Disney’s market share of the box office will be over 40%. One of Bob Iger’s underrated accomplishments as CEO was his focus on “quality over quantity”: during his tenure since 2006, the number of Disney movie releases has fallen from 25 to just 13 in 2019, even as Disney’s share of the box office has doubled.[ii] Disney has already signaled its intention to do the same with Fox’s film slate.

Today, Disney’s market dominance combined with the proposed repeal of the Paramount Rules[iii] is giving Disney unprecedented market power against theatre chains, even as Disney actively directs talent and content budgets away from movies to power Disney+ (even for prized IP like Star Wars) and works to shrink the home video window. Already we are seeing Disney dictate what it can to the maximum, while leaving just enough profit for theatre chains to stay alive.

Source: Deadline.com

Upon the repeal of the Paramount Rules, Disney will be able to bundle its films together (not that it matters), set minimum ticket prices, strong-arm theatres into advertising Disney+, while pitting theatre chains against each other in bidding for the right to show Pixar/Marvel/Star Wars/Avatar/Disney content.

Theatre chains have little choice but to accept the situation or risk nearly half (and the only growing segment) of its attendance with the most popular films. Refusing to show Disney films would essentially bankrupt any theatre chain, given the fixed cost base, while boosting the attendance of competitors.

What does the movie theatre of the future look like

The movie theatre will still exist, albeit at a much smaller scale.

The current “megaplex” with 10 screens in a theatre was built for a time with much higher movie attendance and it is not a bold claim to say that if not for massive long-term leases, the movie theatre footprint will likely be much smaller in the not too distant future.

Major theatre chains are combating the bleak outlook by investing to be the place for a date (through luxury recliners, in-seat service, and fine dining), and expanding internationally where the viewership trends are different. Each complex that still exists will be more immersive with fewer but larger screens, nicer seating (that might rumble) and fine dining options. They will truly be theme park rides because that’s what the audience wants and expects today when they pay US$10 for a ticket.

The additional benefit to reserved seating and subscription programs is that theatres have far more data over moviegoers than before and will be able to provide studios with visitor data for joint marketing that allows, let’s say, Disney to see who is watching Pixar movies but does not subscribe to Disney+, or even create joint programs that allow D23 members to watch Disney movies on the big screen at a discount.

Theatres should drop their resistance on the release window to grow subscription services.

Given the massive headwinds and the changing nature of movie production towards blockbusters with all other formats increasingly going direct-to-streaming, my belief is that theatre chains should drop their resistance over a release window and let it fall to 2 weeks or a month. It will be painful, but this is the only way that theatres will avoid their slate from being cut in the streaming fight and allow them to change the mentality from one of resistance and survival to one of adaptation. Studios like Disney and Universal will preserve an exclusivity window (albeit a much shorter one) for blockbuster films to maximize monetization where a theatrical release still makes sense. More importantly, getting rid of the release window will turn streaming players like Netflix and Amazon into partners rather than foes. As discussed above, it is the number of films that matter for a movie theatre rather than the box office. Netflix alone released 60 English films in 2019, such as The Irishman, that were mostly inaccessible to movie theatres due to their resistance to the release window.

This is where movie subscription passes like AMC Entertainment’s A-List program are key. As MoviePass demonstrated, there is still broad interest in going to the movies at an affordable price. Theatre chains would have access to a much wider library of films and cater to cinephiles who still enjoy the theatre experience. The data would also allow theatres to make targeted suggestions for moviewatchers.

As with the ski industry, subscription passes will grow attendance and drive ancillary sales, solve the perception that going to the movies is expensive, and reduce the industry’s reliance on “hits”. For studios, this is an obvious proposition since the tickets would be 100% incremental.

Does the math make sense? The US box office is expected be somewhere around $12 billion this year. At $25 a month, the industry would need to sell 40 million passes to offset the lost revenue which seems impossibly high in a world where Netflix is only $13 a month.

There are some offsets:

- Disney is already prohibiting its movies from being watched on passes for the first two weeks, and will likely raise prices following the Paramount Rules repeal. This will reduce the # of passes needed to be sold significantly. It will be important for theatre chains to find some way to allow Disney/Fox films to be included in the passes.

- Passes will drive a significant amount of popcorn sales and boost the targeted advertising opportunity.

- There will still be some people who want to go watch a one-off movie. The two-week exclusivity will still give the “must-be-first-to-watch” people a reason to attend, while theatre chains can continue to invest in the “date-night” experience to drive additional sales.

Theatre chains might balk at this prospect, but it is time for the industry to admit that the world has changed and it is up to them to adapt or die.

What does this mean for an investor?

Notwithstanding valuations (I don’t comment on valuations), I find it really tough to be bullish on the cinema industry in North America. The industry will undoubtedly be much smaller in the future, and I believe the pace of the decline will accelerate. It will be particularly painful for small chains and independents who do not have the capability and scale to negotiate with studios on a national basis. The issues are compounded by very long-term leases for large unused screens that are difficult to sub-lease. As we will see in Part II, Cineplex has been creative in handling the leasing issue and I will discuss Cineworld’s acquisition of Cineplex and their strategies in a changing landscape.

[i] This is not exactly apples-to-apples given reporting differences, for example Viacom reports TV licensing revenues together in licensing. The point still holds true however.

[ii] The general consensus among theatres is that although Disney taking control of Fox will hurt film margins, this will be offset by superior marketing and film product by Disney. In small towns in particular, there simply is not that much margin available by small independents for Disney to squeeze.

[iii] Contrary to popular perception, the Paramount Rules did not forbid Walt Disney from owning theatres. The much bigger issue (for theatre owners) is the removal of provisions that prohibit block booking, minimum ticket prices, and circuit dealing. In the motion filed to terminate the Paramount consent decrees, the Justice Department gave theatres two years to “adjust their business models” and basically said, “not our problem, suck it up!”