The primary goal of anyone who participates in financial markets by buying or selling stocks, bonds, options, or anything

else is to make money. This happens when the price of what you buy goes up. Why do prices go up? There are two

primary factors:

Change in Price (Return) = Financial Performance + Change in Sentiment

Financial performance is what the company actually achieves, and involves factors such as a company’s

revenues, dividend policy, and cost structure.

Sentiment refers to the market’s opinion of what an investment should be worth. These may be rational

factors (concerns over the growth rate), or they could be completely unrelated[1]

(i.e. Wall-Street Journal article “Chinese Investors Crunching Numbers Are Glad to See 8”). Changes in sentiment are

reflected in an increased multiple of earnings, revenues or book value. An unpopular company might trade at, for example,

7 times its last year’s earnings, while a very popular one might trade at as much as 30 or 40 times earnings.

Put together, you will make money if the fundamentals perform well, or if the sentiment improves. If both do well, then

you may have the opportunity to make a lot of money.

For certain investments, sentiment hardly matters at all. For example, an investor in a 3-year Canadian government bond

would receive the promised interest and principal payments during the three year period, regardless of the market’s

opinion at any time during the three years. For other investments, sentiment is everything. A bar of gold will not

generate any income for an investor, so the return is purely based on what the market wants to pay for that bar, which is

100% based on sentiment.

The focus for this blog will be on stocks. Stock prices are typically impacted by both sentiment and financial

performance, so it would be a mistake to ignore either one when considering whether to purchase a company’s shares.

Using the above “formula”, the best performing stocks would logically be those with the best financial performance,

combined with large improvements in sentiment. The easier (although still very difficult) part is predicting the future

performance of a company. Investors can do this by analyzing factors such as a company’s competitive advantages over its

competitors, financial condition, capital allocation track records, and projected industry growth rates to reach a

reasonable conclusion about a company’s future financial performance.

With regards to sentiment, the stocks with the highest upside would logically be those that are the most hated, because

an investor would benefit from a reversal in the market’s opinion. As a corollary, such stocks also have the

smallest downside. If the financial performance of a stock remains stable, the only way to lose money on “hated” stocks

is for the market to hate it even more. If sentiment improves slightly, an investor would make money, and if the market

changes its mind and becomes enthusiastic about the stock, an investor would make a lot of money. This is summarized by

the below chart. Indications that a stock is “hated” include a cheaper valuation relative to the industry and broader

stock market, poor analyst recommendations, or a recent decline in price.

Factors affecting the sentiment of a stock range from macro (i.e. general state of the economy) to industry-level

(expected car sales next year) to company-specific (i.e. Blackberry is losing market share to Apple). In my opinion, “big

picture” macro factors such as the general state of the economy and stock market price levels are mostly unpredictable,

and investors should not spend a lot of time worrying about these things. Howard Marks offers a brilliant discussion of

this topic in his book “The Most Important Thing, Uncommon Sense for the Thoughtful Investor”.

However, I believe it is possible to learn about an industry and company’s prospects and form a reasonable opinion about

the company’s prospects. The sentiment about a company’s stock is frequently linked to strong recent financial

performance; so if an investor can find un-loved stocks today with a high probability of strong financial performance

going forward, a lot of money could be made from both the financial improvement and improved sentiment. To me, this is

what investing is all about.

With this framework, an investment can be profitable in many ways. You will make money if a company doesn’t grow at all

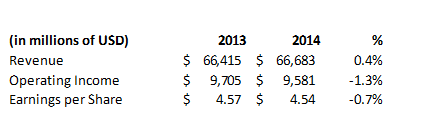

but the market suddenly likes it more. One example would be PepsiCo (NYSE:PEP). From the end of 2013 to 2014, Pepsi’s

results using almost any metric were flat. However, the share price rose by 15% over the same period.

An investor can also make money if a company performs well, with no change in opinion about the stock. For example, from

June 2013 through June 2016, Priceline Group’s (NASDAQ:PCLN) shares rose from around $803 to $1,410, while the multiple

that the market is willing to assign to Priceline remains identical at ~27x earnings for the last twelve months.

Throughout this period, Priceline’s earnings per share rose from $30.40 to $52.46.

On the flip side, an investor would lose money under the following conditions:

- If a company performs poorly, and the market has no change in opinion (Torstar Corporation)

- If a company performs decently, but the market hates it a lot (Home Capital Group)

If a company both performs poorly, and the market goes from loving it to hating it, then an investor would lose

a lot of money, as investors in Valeant Pharmaceuticals discovered in late 2015.

Some investors ignore sentiment completely. These investors are those that were willing to pay 50-60x earnings for

Microsoft’s stock in 1999-2000. In 1999, it was easy to look at the growth of personal computing and Microsoft’s dominant

market share and conclude that Microsoft was a great company with a bright future of growth. This prediction would have

been true. From 1999 to 2016, Microsoft’s revenue more than tripled from $19b to $85b, with net income rising from $7.8b

to $16.8b. However, Microsoft’s share price would not reach its 1999 peak again until October 2015. There is clearly

danger in buying companies that the market is highly enthusiastic about, regardless of the prospects of the company.

Other investors focus purely on sentiment, and buy certain stocks just because they are hated with little regard to

company fundamentals, or even worse, simply because they are loved. Most of technical analysis would fall into this

category. There are also some “value investors” who do this by buying stocks simply because they have low Price/Earnings

or Price/Book ratios, with no view on the future performance of the company. Suppose a company’s EPS fell from $1 to

$0.90. If the share price previously was $10, the P/E ratio would need to rise from 10x to 11.11x in order for an

investor to break even. Given how sentiment and financial performance are frequently linked, it’s not hard to imagine a

scenario where an investor would lose money on a declining company.

Unfortunately, the market is frequently rational and the only time when companies with extremely bright futures are

trading at “hated” prices is during times when everything is hated. Recent examples would be the bear markets in

2002 and 2009. This is why the greatest opportunity for investment is when the future looks most gloomy, and why

investors should always have some liquidity to take advantage of said opportunities. However most years, the outlook is

not so bad. How should one invest in these times? One option would be to simply wait for the stock market to crash. This

is not a bad idea, but it would force you to do nothing for extremely long periods of time, and since I think stock

market crashes are virtually unpredictable, it is not a realistic option for most people.

At Baskin Wealth Management, we believe it is a better idea to hit singles and doubles rather than wait for home run

pitches. We have some companies that have great outlooks (in our opinion) trading at neutral valuations, and some fair

companies trading at “hated” valuations. In Part #2, we will discuss two companies we like that fall into this category

of fair companies trading at “hated” prices.

Ernest Wong

August 23, 2016

Clients of Baskin Wealth Management are shareholders of Priceline, Microsoft, Home Capital

[1] Chinese Investors Crunching Numbers Are Glad to See 8s- http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB117994449875112338