The World’s Most Important Confidence Game: Banks

Like you, I am carrying nicely printed pieces of plastic in my wallet. The green ones are “worth” $20. Well, that is to say, you can exchange them for $20 of other stuff; and you can pay your taxes with them. The value of the plastic, as plastic, is of course pretty much zero. It was not always this way with money. In the Bible, when Joseph was sold into slavery by his brothers, the price was twenty pieces of silver. Some 1,000 years later when Judas betrayed Jesus, he received thirty pieces of silver. (Yes, it is Passover and Easter this week!) At the time of the Napoleonic Wars, a British sailor or seaman who enlisted was given “the King’s shilling”, a large silver coin. It was only in 1971 that the U.S. formerly delinked its currency from gold and silver. Since, then, it’s just been printed paper, or in Canada, printed plastic. Of course, really, money is mostly digital records kept by banks.

The failures of two U.S. regional banks and the forced takeover of a large Swiss bank in March rattled people. The currency system, and the banking system, are ultimately based on confidence. We all know that our banks don’t hold enough currency to pay back all their depositors, if they all asked for their money at once. We accept that, just as we accept that plastic and paper can be exchanged for goods and services, because that’s what makes modern society possible. The Israeli writer Yuval Harari points out the unique and irreplaceable role of money:

“Money is also the apogee of human tolerance. Money is more open-minded than language, state laws, cultural codes, religious beliefs and social habits. Money is the only trust system created by humans that can bridge almost any cultural gap, and that does not discriminate on the basis of religion, gender, race, age or sexual orientation. Thanks to money, even people who don’t know each other and don’t trust each other can nevertheless cooperate effectively.”

When that trust breaks down, really bad things happen. When it is about deposits in a bank, the result is a “run” on the bank. This is what we saw with Silicon Valley Bank (SVB). All of its depositors demanded all their money back at once. The bank, like any bank, couldn’t do it, and failed. It didn’t help that SVB has been described as “a bank run by idiots” that suffered “a bank-run, by idiots”.

When the trust breaks down across a country, the result is hyper-inflation. In Argentina, a country with a horrible history of financial failure, the inflation rate is currently about 100%. Money loses half its value, measured in what it can buy, every year. In Zimbabwe, another very poorly governed country, inflation is currently 230%. Prices go up about 13% per month, every month, doubling in a bit under half a year.

Canada has been lucky in its banking system and its management of inflation. Our last significant bank failure was 100 years ago. (Two small Alberta-based banks failed in 1985). Our banking system is composed of a few very large and very well-capitalized institutions that are very closely watched by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions. Because all of these banks are classified as “systemically important”, they are literally too big to fail. The government will basically move heaven and earth to prevent one of these banks from going out of business. In the extraordinarily unlikely event of a run on a Canadian bank, the Federal government would have no choice but to make all depositors whole, as the US government did in the case of SVB.

Likewise, since 1982, the Bank of Canada has done a very good job of keeping inflation under control. One of the first central banks to have an explicit inflation target (2.0%), the Bank of Canada has worked to keep employment high, economic growth vibrant, and inflation low. That these three goals are frequently incompatible and pull the economic system in different directions is understood.

Since 1992, more than twenty years ago, inflation in Canada has been mostly right around the Banks’ target rate of 2%. That makes the recent spike to 8%, however brief, more shocking. The combination of circumstances that caused that spike are being debated widely. The global COVID pandemic, a major war in Europe, agricultural failures caused by climate change – these factors and others are blamed, in combination, for inflation far beyond anything experienced since the early 1980s. It now appears, however, that inflation is receding quickly, at least in North America, and will likely be under 4% by the summer.

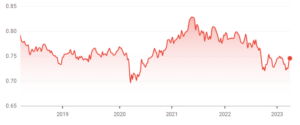

Some of our clients have asked us if it is risky to have money in the bank, or in bonds. We have answered that our confidence in the systemic strength of the Canadian financial system is high, and unshaken. We think that there is no foreseeable threat to our big banks, or to the brokerage houses that they own. We similarly believe that the Canadian dollar is sound, and will continue to trade in the range that has been established over the last five years:

Confidence is a tricky thing. Like a good reputation, once lost, it can be almost impossible to recover. The fact that both the European and US banking systems have survived a crisis of confidence is very comforting. We don’t think that we will face anything similar in Canada, but if we do, our belief is that the checks and balances that are in place will be up to the task. So far, the CEOs of the big Canadian banks report no change in the level of deposits. Most Canadians, like us, remain confident.

David Baskin

Chairman

Media Appearances

Barry Schwartz on BNN – Top Picks & Past Picks – March 20, 2023

Barry Schwartz on BNN – Market Outlook – March 20, 2023

Long Term Investing Podcast with Barry Schwartz

Interesting Reads

Is Generative AI the next consumer platform? – Andrreessen Horowitz